And the work that remains.

The Black Lives Matter movement was born out of the pain and injustice of Trayvon Martin’s death in 2012 and gathered momentum in the wake of the killings of Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Freddie Gray, Walter Scott, Tamir Rice and far too many others. The movement issued a call to action for people everywhere to recognize the reality of institutionalized racism.

Christian leaders around the country saw the movement as a critical opportunity to engage their church in conversations about race and privilege. The Huffington Post reached out to some of these leaders for their thoughts about how Black Lives Matter has changed the church — and the work that still needs to be done.

Rev. Jennifer Bailey

Founder of the Faith Matters Network, fellow at the Nathan Cummings Foundation and ordained itinerant elder in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, Nashville, Tennessee.

The Black Lives Matter movement awoke our national consciousness to the persistent system of white supremacy and structural racism that penetrates each of our institutions. By placing violence against black bodies at the center of the movement, BLM has demanded dignity and respect for those who are often disregarded as disposal. This summer, my denomination was hit particularly hard from the attack on Mother Emanuel AME in Charleston, South Carolina, to the death of Sandra Bland, a young AME woman found dead in a jail cell in Texas. My prayer is that the specific pain and grief experienced in my church community this summer can be catalyzed toward concrete action and advocacy on issues ranging from police brutality to intergenerational poverty.

Credit: Nabil K. Mark/Centre Daily Times/TNS via Getty Images

I think American Christianity has been slow to get on board with the message of BLM out of fear and uncertainty. The gospel message of Jesus was, at its core, about embodying God’s love through affirming the inherent dignity of all peoples in general, and of marginalized peoples in particular. I believe BLM is issuing a challenge to the Church to enter into a deep sense of collective lament for the loss of life, repentance for our complicity in systems of white supremacy and courage to be led by those who may not fit our “traditional” models of leadership. I hope that there will be those in the Christian community who are bold enough to take on this challenge wholeheartedly.

A demonstrator holds a Sandra Bland sign during a vigil near the DuSable Bridge on Michigan Avenue in Chicago. | Credit: Christina K. Lee/Associated Press

Pastor Renita Marie Lamkin

Itinerant elder and pastor in the AME Church, St Charles, Missouri

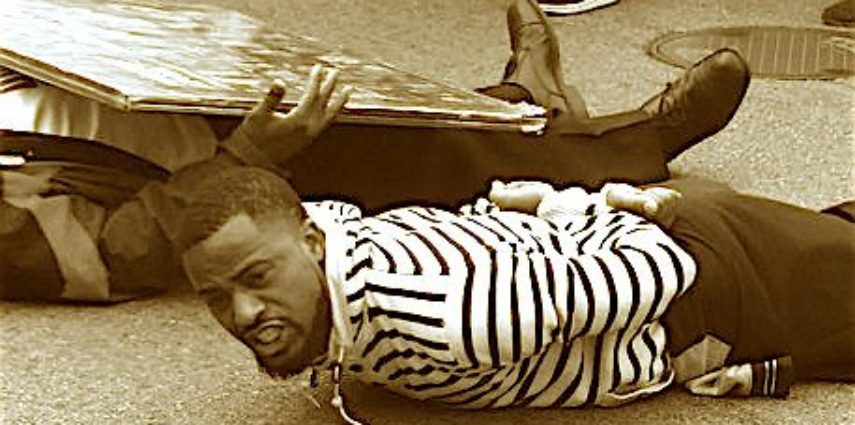

Black and poor residents of Ferguson have been systematically and intentionally targeted, oppressed, vilified and ignored. The government, affluent white business owners and the greater region are no longer able to claim to be ignorant to the crisis of humanity so many have suffered for so long. The police, though having been exposed by residents and the Department of Justice, continue to practice over-aggression when arresting black citizens. At protests, white activists have been spoken to politely, as black activists were pulled off the sidewalks.

There is a deeper sense of awareness in the church to the levels of injustice being suffered by black and brown people in the greater St. Louis region. Churches have engaged difficult and uncomfortable conversations about race, complicities in white privilege and participation in white supremacy. The Church has broadened its embrace of the “other” and has begun celebrating the work of those who are in the struggle for justice. Clergy have been more visible and audible in their critique of the racist systems from which much oppression flows.

But more action is needed. Too often, meetings and community conversations are held in order to delay progress and to give the illusion of progress, all while the community remains broken. So, action to change the system is needed — not Band-Aid actions.

In this Aug. 25, 2014 file photo, Michael Brown Sr. yells out as the casket is lowered during the funeral service for his son Michael Brown in Normandy, Missouri. | Credit: Richard Perry/New York Times via Associated Press Share on Pinterest

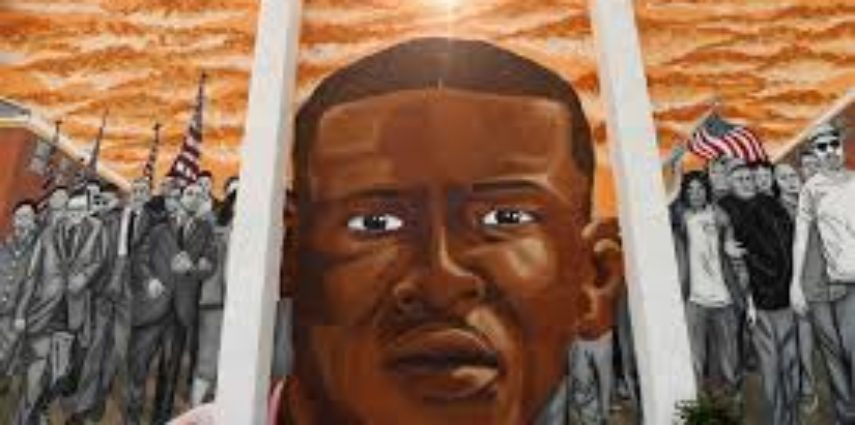

Rev. Dr. Jamal Bryant

Senior pastor at Empowerment Temple, Baltimore

I think the religious community is now more intentionally integrated with the larger community. It took Freddie Gray’s death to realize how large and deep that wedge was. We are building one brick at a time to build up a generation that, generally speaking, wasn’t a part of anybody’s church. They believe in God, but they feel the church has been disconnected from what’s taking place in the community.

Much of what Jesus did didn’t happen in the temple. I think Gray’s death has caused the church to move outside the safety of stained-glass windows and really do ministry on the street.

In our own church, we opened up a Freddie Gray Youth Empowerment Center. We’re feeding 500 kids a day and offering them programs in mathematics, computer skills, fine arts and athletics. Without the Freddie Gray uprising, I’m confident it wouldn’t have happened.

Credit: Leigh Vogel/Getty Images

July had the highest monthly murder rate in Baltimore since 1972. We have a whole lot to do. The national debate is about aggressive policing, but we can’t do that while neglecting young people who are killing their neighbors.

I think Black Lives Matter has changed the black church. It’s given it license to embrace our ethnicity out loud. I think there’s a resurgence of the black power movement from the 1970s that hasn’t been as strong over the last 20 years. This generation has sparked a flame that was going to go out.

Credit: Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

Jamye Wooten

Co-founder of Baltimore United For Change and publisher of KineticsLive, a faith-based news website covering social justice movements

We have seen a strong collaborative effort amongst grassroots and faith-based organizations. From summer camps and freedom schools to urban farming and the opening of recreation centers, many have stepped up to make a change in [the] lives of our youth and community. But the systemic and structural violence still remains — high unemployment, failing schools, vacant and abandoned homes and high rates of poverty still exist.

While I know many individuals of faith that are involved in this movement, the mass mobilization of youth across the nation has challenged many in the church to move beyond their comfort zone, behind the four walls of the church, and to come into the community. My prayer is that the church won’t solely concentrate on charity or social service ministry, something many of our churches are good at, but that they would advocate for just and righteous policies — living wages, affordable housing, quality education and the like.

Baltimore needs to make a commitment to invest in uptown the same way that they have invested in downtown. Black churches must make a commitment beyond charity and social services ministry and begin collaborating and pooling our collective resources for the upliftment and development of our communities.

Judy Scott grieves at the site where her son, Walter Scott, was shot and killed by North Charleston Police Officer Michael Slager, in North Charleston, South Carolina. | Credit: Mic Smith/Associated Press

Rev. Nelson B. Rivers III

Pastor of Charity Missionary Baptist Church in North Charleston, South Carolina, and vice president of religious affairs and external relations at the National Action Network

After the Emanuel Nine, we saw the flag come down. There was an outpouring of goodwill and beautiful words. We now have a body cameras bill for the whole state. But law doesn’t always change police behavior, as we saw in the case of Sandra Bland. We don’t need rhetoric, we need action.

In Charleston County, we still have a deeply segregated school system. Rev. Clementa Pinckney fought hard for the children of Charleston County. It’s easy to make wonderful statements about Rev. Pinckney, but to ignore his mission to bring change to the school district — that’s cheap grace. We need grace that has a cost.

To say that the Black Lives Matter movement has changed the church would make it appear as if, at one point, the church didn’t think black lives mattered. That’s not true. I reject the notion that there’s a generational divide. There were issues of passion and youthful expression at first, some impatience for what they perceived to be a slow process. We aren’t enemies, we’re on the same side. You shouldn’t be speaking about preachers in the church as though they’re your enemies, that’s insulting and disrespectful.

What Black Lives Matter did was push the envelope. They gave life to our leadership. Where we didn’t agree, we’re now able to have a conversation. We work with young people as they continue to do the work we can no longer do.

Jonathan Walton

Project director of InterVarsity’s New York City Urban Project, a faith-based leadership program that trains students to engage and act against injustice

The Black Lives Matter Movement has the potential to turn a moment into a movement, but must expand in depth and breadth to accomplish the task of justice and reconciliation.

First, we must know who we are as people made in the image of God made to work, flourish, rule and create to ensure the working, flourishing, ruling and creating of all of creation. Our identities must be fixed solely in that reality.

Second, we must root our work for reconciliation in shalom and recognize the image of God in every person on the face of the planet. Because as we see ourselves rightly as ambassadors, given the ministry of reconciliation, then we can rightly see others.

Lastly, I believe that we must get as excited about policy shaping as we do about protesting. Personal, relational and systemic sinfulness needs personal, relational and systemic redemption; and that work is little, slow and fueled by prayer, long meetings and relationship building — not just marches, Twitter feeds and shouting matches on- and offline.

Credit: Joe Raedle/Getty Images

Troy Jackson

Director of the AMOS Project, a faith-based effort that organizes congregations to work for racial and economic justice in Cincinnati

What has changed after the shooting of Tamir Rice? My first reaction is that Tamir Rice is just one of the names of those who have lost lives senselessly to law enforcement in Ohio in the past twelve months. There was John Crawford III, Tanisha Anderson, Samuel Dubose. Ohio in 2015 has become Mississippi in 1955. Blacks are killed by police, and it is rare indeed to even get an indictment, let alone a conviction.

Black Lives Matter has served as a prophetic voice to the church and to our society. They are calling people of faith to examine our values, and to decide if we want to continue to be chaplains to an empire that devalues the lives of so many, or whether we will join them as prophets of the resistance. They ask the church a critical question: “What side are you on?” The church can either declare we are on the side of the Exodus, the Resurrection, or we can walk away sad like the rich young ruler, for we have far too much invested in the American empire that is infused with white supremacy.

We must heed the call to prayer, and we must heed the call to presence. As John 1:14 in the Message says, Jesus “became flesh and moved into the neighborhood.” We must be present in our communities, supporting justice leaders, marching, strategizing, praying and bringing the powerful justice narrative of Scripture to bear in a broken world.

These interviews have been edited and condensed for clarity.

Source: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/how-the-blacklivesmatter-movement-changed-the-church

How The Black Lives Matter Movement Changed The Church August 10th, 2015KINETICS